Brain Scans May Predict Math Gains in Children, Study Finds

Brain scans may be able to predict which kids are likely to improve their math skills in school and which ones are not, and they do it better than IQ or math tests, researchers reported Tuesday.

The researchers have been working with a group of kids who started getting brain scans at the age of 8, and who have followed up with tests into their mid-teens.

To their surprise, the researchers found that certain patterns of brain activity when the kids were not doing anything at all at age 8 predicted how much they would improve their math skills over the years. And these scans did so with far more accuracy than did intelligence tests, reading tests or math tests, they report in the Journal of Neuroscience.

While it’s far too soon to stick every kid into a brain scanner, the findings may eventually lead to ways to identify the children who’d benefit most from intensive math coaching, the researchers said.

“I can’t take one child, put the child in a brain scanner and say with certainty this is how the child is going to end up,” said Tanya Evans, a psychiatric researcher who worked on the study.

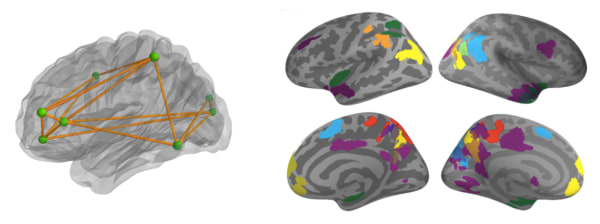

What the study does show is which brain regions appear to be the most important in developing math skills. Evans says the work parallels studies done on kids with dyslexia — a condition that affects the ability to read printed words.

“A long-term goal of this research is to identify children who might benefit most from targeted math intervention at an early age,” said Vinod Menon, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences who led the research.

The team recruited 43 kids with normal intelligence who took tests and sat still for functional magnetic resonance imaging scans, and well as ordinary MRI scans. MRIs can map the physical structure of the brain while fMRI can show function.

The students weren’t thinking about or doing anything in particular. But the research team was able to pinpoint areas of the brain that were more active in the kids who improved their math skills over the next few years.

About half of them improved their skills, and about half of them got worse, Evans said.

“Some of the kids started out really bad and ended up really good,” Evans said. “Some stayed average. Some started out good and got worse.”

Evans doesn’t think this means that math skills are necessarily hard-wired into the brain. She wants to work on ways to improve math skills and to see if the brain structures also change.

“Practice makes perfect in everything,” she said. “We are looking at what types of math interventions are most effective,” she said.

Simple memorization exercises might help, Evans said. And some day, her team hopes to start a study in which younger kids would get brain scans, get the extra math help, and the researchers would scan their brains again to see if their brains did change over the years.