Grooming Is a Gateway to Sexual Abuse, But Schools Are Virtually Powerless to Stop it

In countless cases in which educators abuse students, they first “groom” them – by showering praise, offering rides home and more. But because those actions aren’t illegal on their own, it’s difficult for schools to identify the problem and do anything about it.

Looking back, Gabriel Huerta wonders whether an interaction in the Bonita Vista High School parking lot that might seem harmless on its face was the moment his school band teacher began grooming him for sexual abuse.

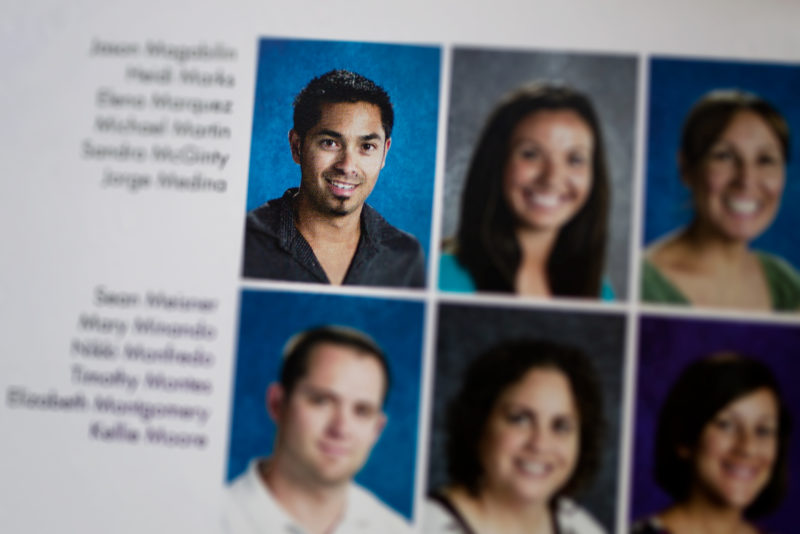

Huerta recalls he was walking his tenor saxophone home, and the teacher, Jason Mangan-Magabilin, was walking to his car. Huerta says Mangan-Magabilin made it a point to call out his name across the lot and tell him he did a good job at band practice that day.

“It’s not so much what he said but how he said it,” Huerta said. “That’s when it started to feel special. It’s one thing to be positive and encouraging, but in a parking lot as I’m about to go home with no one else around … ”

Huerta said he now looks back at his early interactions with Mangan-Magabilin with a critical lens.

“That could’ve been harmless if it was right outside the band room or I was a little closer, or there was someone else and he said it to both of us. But I really started to feel his energy focus on me.”

Huerta said from that moment on, he started to look up to Mangan-Magabilin.

“I literally had to because he was on a ladder in marching band,” Huerta said. “I’m looking up at him conducting and something clicked in my head: Not only is he openly gay, but everyone trusts him.”

The parking lot interaction and others that preceded years of sexual contact between Huerta and Mangan-Magabilin illuminate how difficult it can be for school officials to identify and punish so-called grooming behavior by predatory educators.

None of those behaviors – like giving compliments, gaining a student’s trust or paying special attention to a student – is illegal. But in many cases in which public school employees sexually abuse students, grooming is a precursor to serious crimes.

In Huerta’s case and many others across the San Diego region, public school teachers used grooming to create deep emotional bonds with their victims and encourage them to let their guard down. Then they abused them.

Huerta and others say they did not even recognize at the time that what was happening was abuse.

Under the U.S. federal Title IX law prohibiting sexual discrimination in schools, school districts are required to categorize grooming by employees as sexual harassment and investigate those claims like they would any other incidents of sexual misconduct. Yet many of the hallmarks of grooming can easily be explained away or even mistaken for exemplary teaching – the exact opposite of what it is.

Mangan-Magabilin initially agreed to answer questions by email, but declined after we sent them. The Sweetwater Union High School District did not respond to multiple requests from Voice of San Diego.

How Grooming Works

Diane Cranley, president and founder of Talk About Abuse to Liberate Kids and a prevention child abuse consultant, works with California K-12 school administrators to train school employees on recognizing “grooming” signs and how to implement formal policies to prevent it.

“I think the challenge is most educators don’t know the grooming signs. … Sometimes there’s true cover-up, but sometimes it’s ignorance,” Cranley said. “I hear from educators, ‘I would report it if I suspect it, but I don’t really know the signs.’”

Nor does the Education Code requires educators to learn about child abuse, but not specifically about grooming. Cranley said school districts need to provide additional information to school employees on grooming.

“We’re literally missing the mark on this training that people have to take every year,” Cranley said. “When we first put mandated child abuse reporters in place we saw that kids were getting abused at home and while that’s true; the training hasn’t changed much as far as laws and training to recognize grooming by teachers.”

Cranley said the profile of a predatory teacher and the ways they groom young people for sex is not much different from how authoritative figures operate in another institutions like churches, athletic programs or groups like the Girl Scouts and Boy Scouts.

But there is one thing that makes abuse by educators unique, she said: near constant access to victims.

“Even in churches, you might only have access to children once a week on Sundays … whereas with schools, it’s five days of the week, nine months of the year,” she said.

Educators who exploit young people for sex are often well liked and respected by peers and parents at the schools they teach because of the close bonds they are able to form with school children, she said.

And the ways they take advantage of students are clear.

An educator who aims to exploit a young person for sex might single out a student by isolation, offer them personal attention, buy them gifts, chat with them through text or social media messages, give them rides to and from school without another adult present or introduce physical touch with seemingly innocent gestures like a hug or whisper in an ear.

Their victims are often the most vulnerable children – those who may have a void to fill. Those students form close relationships with those educators and don’t know they’re being abused.

That is in part because predatory teachers often persuade their victims not to share any details about their interactions and to deflect any questions about it.

The abusers often enlist other unwitting adults who allow them to create those close bonds. They may form close relationships with the student’s parents to build their trust, and convince other educators they are the student’s friend or mentor.

‘I Knew He Was Confident That No One Was Going to Question Him’

At Bonita Vista High School in Chula Vista, Mangan-Magabilin was an openly gay band director who was close with students and parents in the band program and who elevated the program to a level of prestige.

“He knew how to play the part when he was in the spotlight. He was a good person in the community,” Huerta said. “He was openly gay, Filipino-American and there was a certain charisma to him. Everyone wanted him to succeed.”

Huerta described himself at 15 as a quiet, hardworking “A” student who found creating music to be an outlet of relief. Huerta said the saxophone was his musical instrument of choice because it required him to breathe deeply to create music. Those deep, concentrated breaths helped Huerta cope with the fallout of family problems at home.

In 2008, Huerta joined the Bonita Vista High School band the summer before 10th grade. The next year, Mangan-Magabilin appointed him drum major, one of the highest leadership roles in the band. He said that even before he got the position, his classmates had become suspicious of the favoritism Mangan-Magabilin showed toward him.

Huerta was in nearly every music ensemble at the school and saw Mangan-Magabilin almost daily.

“I didn’t have any other figures around,” he said. “I really enjoyed that time, but then always after people pack up their instruments and go home, and I’m with him.”

Huerta said sophomore year he started to develop a crush on Mangan-Magabilin and looked to him as a mentor. Mangan-Magabilin gave him his phone number and would hug him often.

Those hugs and their interactions turned intimate when the teacher began to give him rides home during his junior year.

Huerta recalled Mangan-Magabilin told him that if he got straight As his fall semester of junior year, he would take Huerta out for a celebratory lunch – just the two of them. When Huerta got the grades, Mangan-Magabilin made a day of alone time out of it, Huerta said. Mangan-Magabilin took him to his barber in North Park and to lunch in Hillcrest and to see “Avatar” in Plaza Bonita, Huerta said.

“In the moment I felt special; I felt like I had a friend for the rest of my life; I felt like this person has my back; I felt like I was starting to feel love,” said Huerta.

Huerta said one day he went to Mangan-Magabilin’s house with another band member to help the teacher with housework. That student went home early, and the two were alone together.

Huerta recalls he and Mangan-Magabilin were laying down on the couch together when Mangan-Magabilin began tickling him. Huerta ended up on top of Mangan-Magabilin and the two began dry-humping, Huerta said.

“From dry-humping I experienced my first ejaculation. I had never masturbated before. When I told him what happened, he teased me in an endearing way and gave me his boxers to wear,” said Huerta. “Then he drove me home.”

The next day, Huerta recalled, he was in the band room during lunch with other classmates. In front of other students, Mangan-Magabilin called out to Huerta from his office.

“When I went in, he said, ‘I have something for you,’ and had my boxers folded on his desk. I grabbed them and shoved them into my bag; I was embarrassed. Since he was so upfront about it, I knew he was confident that no one was going to question him,” Huerta said.

Huerta said Mangan-Magabilin seized on Huerta’s anxiety about his parents’ separation and adult responsibilities at a young age.

Their interactions turned sexual in Huerta’s senior year, when he was 17 and Mangan-Magabilin was 32. They’d perform sexual acts on each other – including in the Bonita Vista High School band room with the doors locked, the lights off and a cabinet blocking the window into Mangan-Magabilin’s office, the main band room school copy room, music library, racquetball courts and Mangan-Magabilin’s home, Huerta said.

But Huerta said the two waited to have penetrative, unprotected sex until the month after he turned 18, during Huerta’s freshman year of college.

Huerta now says he feels Mangan-Magabilin robbed him of basic parts of his sexuality, like the experience of a first kiss, first boyfriend and first sexual encounter.

The Predator’s Playbook

A sad irony of stories like Huerta’s is that while predators convince their victims that their bonds are special and unique, they actually follow a remarkably consistent playbook.

At Mar Vista High School in Imperial Beach, a retired Marine substitute JROTC teacher who ultimately pleaded guilty to statutory rape of a 17-year-old student first gave her rides to and from school and texted her cell phone, according to a civil suit filed by the student.

At La Costa Canyon High School in Carlsbad, an English teacher encouraged a student to communicate with him using his personal email address, enlisted her as his teacher’s aide, shared books and music with her and invited her to meet up off of school grounds before initiating sexual acts with her, the student told VOSD.

Both teachers ultimately lost their teaching credentials, and the Sweetwater Union High School District and San Dieguito Union High School District paid the former students settlements after they sued the districts over the abuse.

In all those instances, the students involved said they weren’t physically forced to have sex but that the male teachers preyed on their vulnerabilities.

Each of them tried to protect those teachers from being punished or removed from their teaching positions because they’d been coached to do so.

The La Costa Canyon student denied anything inappropriate had happened between them to school officials, and secretly alerted the teacher to an investigation into the interactions between them, stalling the probe. When a school volunteer advised the Mar Vista student to report the abuse to police, she said she was concerned he would lose his job, according to records obtained through a public records request from the district. A text message she sent to that volunteer reads, “I’m not lying JUST for him. I’m lying for myself, and for him and for the unit, and school, and Cadets and the program.”

Huerta said he too regularly denied anything inappropriate was happening between him and Mangan-Magabilin when observers raised concerns, including a student who submitted an anonymous letter to Mangan-Magabilin, a parent, a counselor and math teacher who all raised concerns at various points and even Mangan-Magabilin’s fiancée at the time.

“A lot of people didn’t want to vocalize their suspicions because he was an openly gay teacher mentoring an openly gay student,” Huerta said. “And no one wanted to accuse this minority at the time. There’s not many teachers that could be mentors to openly gay students.”

Few Districts Have Policies Spelling Out Boundaries

Huerta’s case in particular demonstrates the difficulties districts face in investigating and disciplining educators for grooming behaviors alone.

Huerta’s parents eventually raised suspicions of their son’s interactions with his band teacher to school officials. He said his father was initially suspicious, but his mother saw Mangan-Magibilin as his mentor and did not want to take that role away from him – until they both grew concern.

In August 2010, Huerta’s parents presented evidence of phone records that showed Huerta talked to Mangan-Magabilin on the phone often late into the night – sometimes exceeding 2,000 minutes in one month – to BVHS principal Bettina Batista and expressed concerns about the teacher spending alone time with his son.

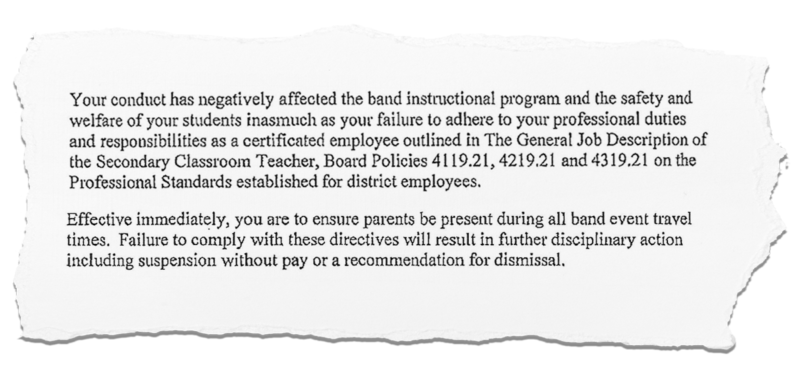

Batista agreed the teacher’s interactions with Huerta could be violation of his professional duties and responsibilities. She told him not to contact Huerta outside of instruction, not to be alone with Huerta under any circumstance and to not provide car rides to or from band events, according to a district warning letter obtained by VOSD.

Two months later, Huerta’s father told Batista he was still worried about their interactions. He and Huerta’s mother drafted a memo reiterating that Mangan-Magabilin should not contact Huerta outside of school.

Mangan-Magabilin signed the document in November 2010. Huerta’s parents asked Batista to sign it, but she did not. But that didn’t end things. Batista continued to warn Mangan-Magabilin about his interactions with Huerta until the end of that semester, but allowed him to continue teaching until 2016, when Huerta reported the abuse to police.

That’s not unusual. It’s rare that instances of grooming alone result in removal from school districts.

Two teachers at Westview High School, for example, sent sexually suggestive text messages to students but were allowed to continue teaching.

Few schools across the state have policies in place addressing student-teacher boundaries, or communications via text, email or social media.

The California Department of Education does not have any rules in place spelling out instances in which a teacher or school employee can be removed for grooming behavior.

Sweetwater Union High School District, which employed Mangan-Magabilin, does not have a clear policy outlining employee communications with students despite facing numerous lawsuits in recent years from students abused by educators who used grooming techniques like texts and emails.

Grossmont Union High School District is one of the few school districts in San Diego that has a policy outlining teacher-student boundaries. It defines unacceptable teacher-student behaviors as “making sexually inappropriate comments, becoming involved with a student so that a reasonable person may suspect inappropriate behavior and intentionally being alone with a student away from school.”

Few districts across the state, including Redlands Elementary School District and the San Francisco Unified School District have policies that clearly address consequences employees could face for exploiting their roles as child mentors.

More than 95 percent of the state’s education agencies, including school districts and county offices of education, rely on the California School Board Association, a non-profit education association to provide guidelines on content and policy language. The organization does not have a policy specific to student-teacher boundaries, but one is in the works, said a spokesman.

Despite the lack of guidance, Cynthia Butler, a spokeswoman for the California Department of Education, told VOSD that grooming in schools does fall under Title IX regulations, the federal civil rights law that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in federally funded education programs.

But what exactly gets categorized as “grooming” or inappropriate conduct between teachers and students is up to each local agency, Butler said. The definition of conduct between teachers and students, investigations and employee discipline are also left to individual schools and districts, she said.

Butler said parents, community members, students and educators should first take complaints of sexual grooming to a school or district, which are obligated to conduct an investigation.

Based on the findings of that investigation, the school should aim to “end the harassment, eliminate the hostile environment, prevent its recurrence, and, as appropriate remedy its effects,” according to the California Department of Education’s Title IX website.

If a parent or community member believes that a school is not handling a complaint of grooming properly, that person can file a report with the Education Department or at the federal Office of Civil Rights, Butler said.

A spokesman from the U.S. Department of Education told VOSD that although Title IX’s prohibition against sexual harassment does not extend to legitimate nonsexual touching or other nonsexual conduct, in some circumstances, the department acknowledges “nonsexual conduct may take on sexual connotations and rise to the level of sexual harassment.”

“For example, a teacher’s repeated hugging and putting his or her arms around students under inappropriate circumstances could create a hostile environment,” the spokesman said. That hostile environment would “deny or limit a student’s ability to participate in or benefit from the school’s programs or activities” and require a school to respond.

The Legal Case

Huerta said those sexual interactions with Mangan-Magabilin continued while he was college, from 2011 to 2014. Nearly two years after the two last interacted, Huerta was teaching at an arts-focused high school where he was required to take a mandated child-abuse training – one that mentioned the signs of grooming.

Huerta said the training helped him recognize the signs of his own abuse. “I had about a year and a half where I wasn’t being groomed, psychologically conditioned, sexually abused anymore,” Huerta said. “I had time for my mind to gain clarity.”

In July 2016, Huerta reported Mangan-Magabilin to the Chula Vista Police Department. Only then did the district remove Mangan-Magabilin from the classroom.

He was arrested and charged with nine counts of oral copulation with a minor and four counts of sexual penetration by a foreign object with a minor. He pleaded guilty to two felony counts and was sentenced to one year in jail followed by two years of probation. His state teaching credential was revoked by the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing in April 2017.

Huerta sued Mangan-Magabilin and the Sweetwater Union High School District in December 2016, claiming sexual harassment and the district negligently hired and retained Mangan-Magabilin among other claims. The district and Mangan-Magabilin agreed to pay Huerta $650,000 to settle those claims, as first reported by NBC San Diego.

Moving Forward

In 2018, Huerta visited the band room where he says Mangan-Magabilin molested him repeatedly during his high school career.

He said during that visit, he vividly remembers a poster of support for the band director hanging from the wall – along with numerous trophies and awards the band had won under his direction. The poster was signed by “Club Blue” band members at the school – member of that program appeared at Mangan-Magabilin’s sentencing in support as well.

Huerta says he now plays the saxophone occasionally with friends he remains in touch with from the BVHS music program. He said he hopes to one day revisit the instrument without triggers of the abuse.

Huerta works at a local law firm in San Diego, the same one that represented him in his case against Mangan-Magabilin and the Sweetwater Union High School District.

He said he hopes his story will empower other students to recognize the signs of grooming in their schools.

“It wasn’t about him getting justice with him going to prison, or me getting damages with the civil suit,” he said. “It’s about me getting the word out there. Victims need to see what it looks like.”