Why have children? You asked Google – here’s the answer

People who don’t have children often allude to, or openly voice, the idea that other people – society, the world, their parents – think they’re selfish. Apparently this view does exist, as illustrated by the story of Holly, who told BBC news that she never wanted children and got the kind of abuse on social media normally reserved for people who leave dogs in hot cars.

I cling to the idea that people who care that much about another person’s reproductive choices are rare, and furthermore, given the misogynistic nature of the abuse, that the real “selfishness” lay in her being a woman, daring to say anything at all about what she did or didn’t want.

But let’s say, for the sake of argument, that there is a reputable tranche of opinion that finds childlessness selfish; by the same logic, having children is selfless, its role both demonstrative (I am not selfish) and altering (I will become less selfish). The first doesn’t matter, and the second isn’t true.

Sure, you’ll subsume your own needs to those of your child. But as a household your requirements from the outside world will become only more pronounced. So people’s experience of you, whether you’re the mother of a newborn making a noise and taking up space, or the mother of a seven-year-old, wishing that everybody else would just put your seven-year-old first for once, will be that you are more of a pain in the arse, more demanding, more self-righteous and less accommodating, than you were before.

There are some caveats. You might be manifesting an intra-familial selflessness if your parents desperately want grandchildren, say, but pleasing your parents isn’t a good reason in itself. (It’s possible, too, that they don’t want grandchildren as much as want you to be happy. The chances are that you are the best thing that ever happened to them.)

It’s open to debate what kind of member of society you become. In the respect that, to save your own child, you would kill and eat somebody else’s – which you probably wouldn’t on your own account – you are less pro-social; but now you’re more invested in creating and maintaining a world in which nobody has to kill or eat anybody, so in that sense, you’re more.

A lot of what parenting brings out in you is bound to be circumstantial, but I’d stick my neck out and say that the situation has to be so dire to bring out the worst in you that it’s fair to expect it to bring out the best.

There’s a macro-selflessness – having children so that someone’s working to pay your pensions, and to prevent species suicide – but it doesn’t stand up unless you envisage a serious danger that everybody else is going to stop having children. There follows a freeloader argument, that you’re offloading your responsibilities to mankind on to other people. But none of this stands up unless we accept procreation as a burdensome rather than a pleasurable act.

The parenting discourse is inconsistent, on the one hand insisting that there is no greater bliss while on the other claiming it as an act of altruism. The defence that sometimes it’s one and other times the other, is weak; if it’s a pleasure at all, it doesn’t count as an act you’ve undertaken out of duty. Ultimately, there would only be a deontological argument for child-bearing if the world had a particular call for your children above other people’s, which there isn’t, or we had established beyond doubt that people don’t enjoy it, which they do.

People love having children. So the question is, why? Is it a grand delusion, a memory wipe about what life was like before? Is it, as the fiction writer Lorrie Moore once said, that children destroy everything else in your life and then become the best thing in it? Or are they a furnace of purpose and fulfilment, where previously there were only spot fires of miscellaneous interest?

There’s no way to evaluate things such as purpose and fulfilment as universal qualities: you can only gauge the strength of your own feelings. I can’t tell you how great my sense of purpose is, relative to yours. All I can say is how great mine is relative to how it was before. So I can tell you how much it completes me – and at the end of a long night, this is the cul-de-sac some parents disappear down – but that has no application broader than: I was a bit aimless before; now I have aim.

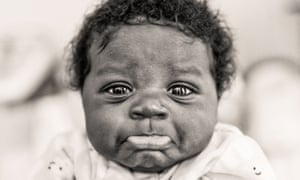

There is no rational level on which this decision makes sense, in other words; but I think the problem here is with the Enlightenment split of mind and body, which leaves us unable to articulate the importance of basic things that our bodies understand: it is obvious the pleasure that children bring you, and obvious how important and untransferable that is. Think of (or trust me on) the bone-deep comfort of holding your child. It doesn’t work with anyone else: it’s relationship specific, and you don’t get the same feeling from hugging your parents, so it’s clearly a one-way street.

Even once your children are old enough to resist you with kicking and insults, you know at a cellular level what the purpose of this relationship is. There are cute things they do – speaking for my own, I find the sight of them singing to songs they don’t know the words to worth the entire fandango – but bring any of that up and you will get a trite line about how uncles and grandparents get the same joy and can hand them back at the end of the day.

You might just as well say, why fall in love when you can be friends? Love is a whole shitstorm of anxiety and vulnerability, poor judgment, one arm hanging off with the fierce gusts of luck and chance and other people blowing straight into your open wound. You would be far better off with a nice, level friendship, with mutually respectful boundaries and cooling-off periods.

The fact that there is no backstop, no end of the day, no rising above it, no reservation – the very fact that it is so illogical, from a self-interested perspective – is the precise point of doing it.